royce wells

Speculation, Innovation and a Gold Rush

Tuesday, July 27, 2021 · 5 min read

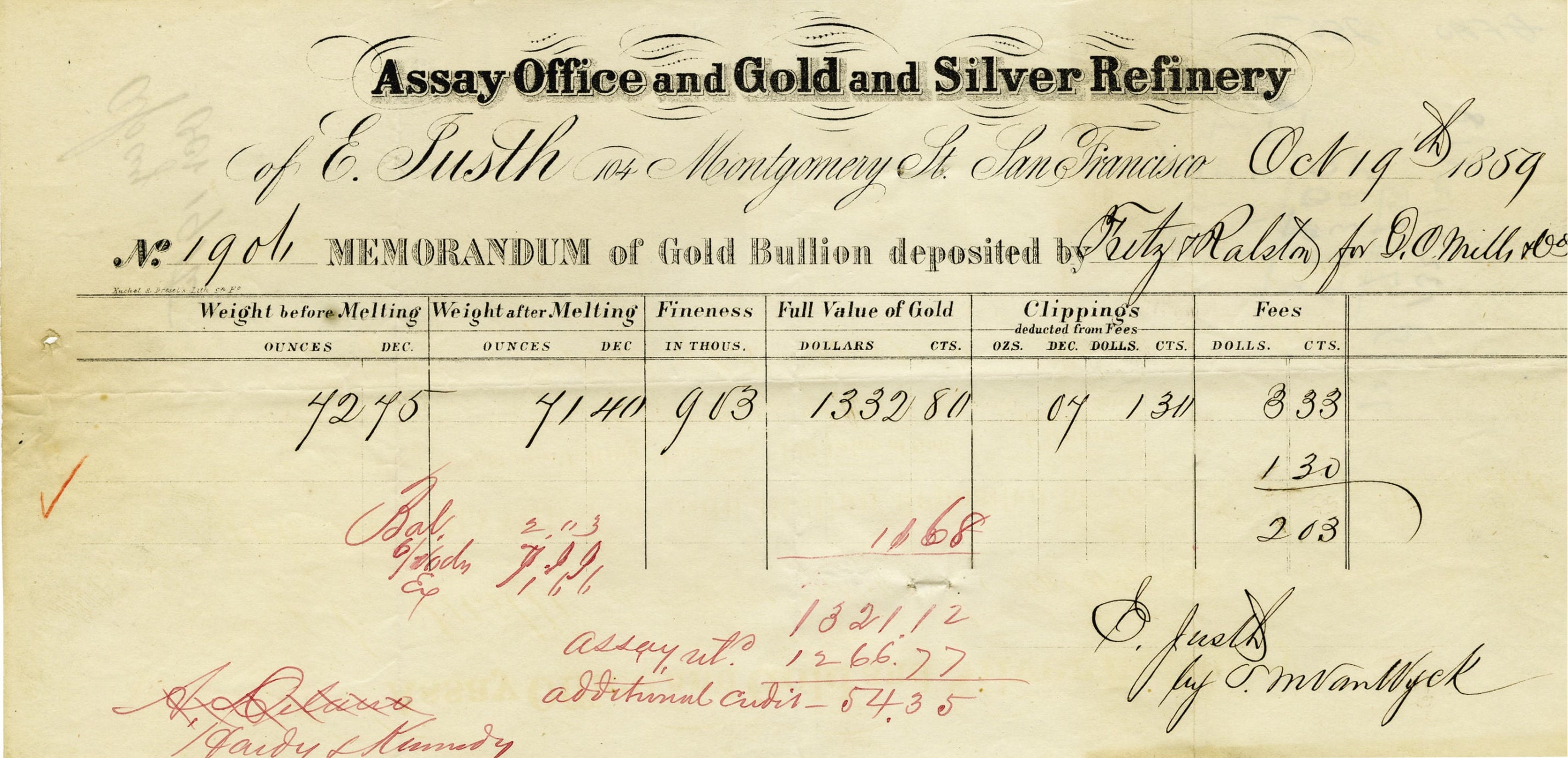

In the 1850s, San Francisco’s Daily Herald reported that “No day so gloomy has been witnessed in San Francisco since that disasterous fire of the 4th of May, 1851. Every bank was said to have suspended, and rumors of mercantile failures-most of them false, we are glad to say-came thick and heavy in the afternoon.” From Hard Money to Branch Banking: California Banking in the Gold-Rush Economy

It was the culmination of years of credit speculation and growth driven by the California Gold Rush. Growing up in California, the gold rush takes on a bit of mythical grandeur in the history of the state. Less talked about was that the gold rush was financed with tons of speculation. Then in the aftermath of a short lived boom the nascent financial system quickly collapsed. The companies and financial infrastructure that were left became the foundation of San Francisco as the finance hub of the American West.

An 1851 painting shows a line of bank offices on Montgomery Street, hailed as the Wall Street of San Francisco.

California Historical Society

An 1851 painting shows a line of bank offices on Montgomery Street, hailed as the Wall Street of San Francisco.

California Historical Society

The short version of the story is that the gold rush created a huge influx of people and business activity, much of it financed by loans from early banking institutions. Many of these weren’t really banks, but various merchant and trading companies that extended credit to individuals and businesses on the western frontier.

Financial services boomed, and early financial technology looked to bridge the gap between capital in the East and new startup businesses in the West. Merchants and suppliers took in gold for depository receipts. The gold moved back East slowly, but money and goods came (on credit) as the news reached around the world. There was ridiculous price inflation every where from Hawaii to Missouri as new money flooded the markets.

The depository paper from California, backed by gold reserves, was mixed with out-of-state “foreign” bonds and traded in a large secondary market based mostly on brand reputation. In turn, this commercial paper served as collateral for more loans, financing even more business activity.

California itself was irreversibly changed. In 1848, California was technically still a part of Mexico. By the time gold fever broke in 1855, California was an American state. San Francisco’s population grew 100 times over. Montgomery Street was heralded as the Wall Street of the West. The most prominent new banks built out immense offices, symbols of security that served as advertising for new deposits.

While partnerships were the primary method of business organization in the 19th century, the new ventures in California were mostly formed as vehicles more similar to joint-stock corporations. These companies were mostly set up to pool community capital, members contributing anywhere from $20 to $2,000 for stock in a joint venture organized for the express purpose of striking it rich in the West. On January 24th, 1849 the New York Herald wrote that there were some 47 companies set to take up the search for gold in California. A few days later they reported that an additional 10,000 had “sprung up like mushrooms—all a lot alike.“ Capitalism Comes To the Diggings: From Gold-Rush Adventure To Corporate Enterprise

This kind of speculative copying is something quite interesting to me. At some level there was good money in the California Gold Rush. But not enough to sustain the level of activity that actually came.

Fortunes were said to be made in a day, and the news spread worldwide, attracting even more capital looking to make big returns in California. People took on immense leverage to start prospecting, mortgaging their homes and collecting outside investment to procure the capital to set up and mine for gold.

Most everyone lost their shirts in spectacular fashion. Maybe slightly hyperbolic, but the crash did wipe out the capital of a number of banks.

The activity, in the ethos you would expect from a literal gold rush, was highly speculative. Folks were lending out money to enter mining and other business ventures with the promise of repayment fueled by a hope expectation that the boom years would continue indefinitely. Of course, the bust came rather quickly. There wasn’t enough gold to sustain the level of activity from the early years. By the mid 1850s much of the market had been shook out as loans turned bad and there was a series of runs on institutions that had been extending credit.

While the vast majority of the financial businesses will be remembered only in obscure papers drawing from California business archives, or lost totally without meaningful surviving records, there was one bank that came of age, grew and survived past the fallout. That would be Wells Fargo, now the third largest bank in the United States. Founded in 1852 as a shipping company for gold before quickly pivoting to banking services, one of the most dominant financial institutions in America was born out of the speculative cycle driven by the gold rush.

San Francisco, a sleepy backwater bay town in the 1840s, became the financial center of the early West. California became the 31st state, ahead of almost all the midwest. There were financial innovations in everything from depository vaults to shipping insurance to equity joint ventures. The early financial infrastructure of California and the American West is a direct result the inflow of speculative capital from the rush for gold.